On Syria, Labour has been here before

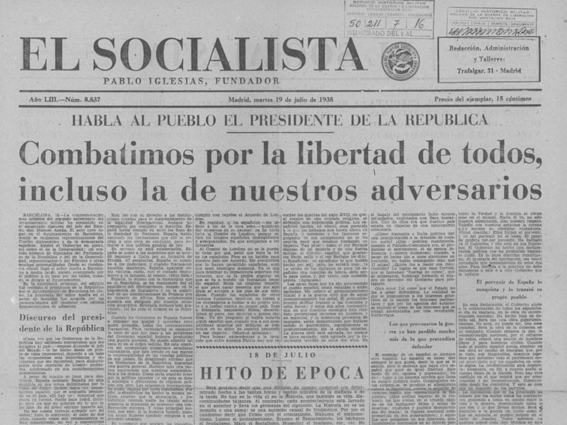

Next July marks the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish civil war. Over three years, General Francisco Franco’s nationalist army unleashed what became known as ‘the white terror’ as it sought not simply to conquer territory held by the Republican government, but to subdue, subjugate and terrorise the civilian population.

In villages and towns across the country, Franco’s fascists showed neither mercy nor shame. As the self-styled Caudillo’s press attaché told an American journalist, they had ‘to kill, to kill and to kill’ their ‘red’ enemies. They would, he pledged, ‘exterminate a third of the masculine population and cleanse the country of the proletariat’.

The nationalist forces were true to his words: union officials, left-of-centre politicians, teachers, doctors, freemasons, even priests were murdered. As Anthony Beevor writes in his magisterial history of the conflict: ‘In fact, anyone who was suspected of having voted for the Popular Front was in danger.’ Despite its professed defence of Catholicism in the face of its ‘godless’ secular Republican enemies, rape was a powerful weapon in the nationalists’ arsenal: ‘Your women will give birth to fascists,’ they daubed on the walls of villages as they advanced on Madrid.

Unsurprisingly, intellectuals were a particular target. Perhaps the best-known victim of the terror, the poet Federico Garcia Lorca, was said by one of his killers to have done ‘more damage with his pen than others with their guns’. Not for nothing did Franco’s psychopathic henchman, General Millan Astray, frequently lead his supporters in a chant of ‘Viva la muerte, viva la muerte, viva la muerte’ at public appearances.

Four months ago, over 1,000 people crammed into the Adelphi ballroom in Liverpool to hear Jeremy Corbyn speak. As at many of the now-Labour leader’s rallies, there was a hearty rendition of the Internationale, the 19th century socialist anthem which became the rallying cry of the Republicans during the Spanish civil war.

The conflict continues to hold a special place in the hearts of the left: while the western democracies backed a policy of non-intervention, thousands of ordinary men and women from across Europe and the United States joined the International Brigades to fight Franco. Unlike their leaders, they could see, as one British volunteer, the future trade union leader Jack Jones, later put it, that ‘those battles were the first battles of the second world war’.

The civil war in Syria is not comparable to that of Spain: despite the fact that terrible atrocities were committed by some of its forces, the Republican cause was one to which the left could ally itself with relative ease. With the voices of the peaceful demonstrators who came out on to the streets of Damascus in March 2011 to oppose Bashar al-Assad long stilled, the Syrian conflict lacks that Manichean clarity.

The pitiless treatment of innocent civilians characterises both the Assad regime and Islamic State, even if ‘viva la muerte’ might trip more easily off the tongue of a jihadist than a Ba’athist. Thus many of those who urge caution with regard to intervention in Syria are right to point to the extreme complexities of the conflict.

Nonetheless, for nearly five years the war in Syria has presented the Labour party with the same dilemma it faced in the 1930s: are words enough? Are warm words of sympathy for the victims and tough words of condemnation for the perpetrators sufficient? Labour initially backed non-intervention in Spain: a position it abandoned with the growing realisation that Germany and Italy were blatantly flouting it and that the policy thus amounted, as the Labour member of parliament Philip Noel-Baker argued, to a ‘hypocritical sham’.

Those words might aptly define Labour’s approach to Syria. In August 2013, the gassing of 1,400 people in Damascus by Assad stirred the party only to a vigorous call to inaction. Despite the refugee crisis, the death of a further 100,000 people and the rise of Isis in the chaos caused by the ongoing conflict, Ed Miliband continued to trumpet that he had ‘stopped the rush to war’ in Syria long after the consequences of the House of Commons’ decision to look the other way were all too readily apparent.

The same bizarre logic was evident in the now-deleted tweet of the shadow international development secretary, Diane Abbott, who suggested in September: ‘I remain strongly opposed to military intervention in Syria – it is only a matter of time before civilians are harmed.’ Such a sentiment is unsurprising: Abbott recently chaired a Stop the War Coalition meeting on Syria which did not include a single Syrian on the panel, and at which Syrian refugees in the audience were not permitted to join the discussion. Some may fear that it is the Stop the War Coalition’s Andrew Murray who is now writing Labour’s foreign policy, but this comes right from the pages of Lewis Carroll.

Labour’s tragedy on Syria will no doubt turn to farce as those who insisted loudest and longest on the importance of a United Nations mandate quibble over the precise meaning of the security council’s call to combat Isis ‘by all necessary measures’ and abandon Hilary Benn’s carefully constructed approach of marrying military action with progress towards a political solution.

For five years the west has fiddled while Syria has burned. The conflict there is, though, no longer about a faraway country of which we know little. Last month, it was the people of Paris who came under attack. If we cannot rouse ourselves to more than gestures of support for our neighbours across the Channel, we should think of ourselves: next month, it might be football fans at Wembley, concert-goers at the Hammersmith Apollo or diners in Soho at whom Isis strikes.

Airstrikes alone will not defeat Isis and bring an end to the civil war in Syria. But they will do more to show our solidarity with the peoples of France and Syria than a tricolour twibbon. It is to Jack Jones, not Andrew Murray, that Labour should look for inspiration at this perilous moment.

———————————

Robert Philpot is a contributing editor to Progress

———————————

Vera Brittain – the mother of Shirley Williams – was a member of the Labour Party in the second world war. She was a pacifist…. a real pacifist. She took an absolute moral position against any kind of killing.

Some people respect her. I think her position is, in the real world, as morally ambiguous as those peace-loving people who supported the killing of Nazis in battle. In the end, pacifism has not stopped wars and may not prevent them. So in the end, pacifism has left other people to do the dirty work. That is morally ambiguous.

The difference between Vera Brittain then and the Labour Party now is that Vera was largely abjured by the party while today a de facto pacifist position seems to have support within the party for now.

But de facto pacifism (= I am not prepared to see force used except under conditions that are impossible to meet) is as morally ambiguous as real pacifism – both end up letting others do the dirty work.

An opposition party that is ruled by moral absolutes is not a “government in waiting”. It is a religion. Progressive government requires navigating moral ambiguities and also navigating political ambiguities. That means there is always a risk of failure. But doing nothing concrete means there is a certainty of failure.

Thank goodness this was recognised by anti-fascists in Spain in 1936 and in the rest of Europe in 1939-45.

Words are not enough – but bombs will solve the problem. Better to do something stupid and counter-productive – than to be seen to do nothing at all?

Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya have all been utter disasters. Spain is not remotely relevant to the situation in Syria, except in so far as bombing and drone attacks have replicated Guernica for year after year in country after country and acted as a recruitment mechanism in all of them for ISIS and other radical groups.

An exceptionally lazy article. Unfortunately, far too common on this website! Lacking any serious analysis, or indeed insight but perhaps only to be expected (with the occasional rare exception), from a perhaps moribund organisation, with an extremely limited pool of contributing authors?