Labour’s forgotten leader deserves better than to be airbrushed from the annals of the party’s history, argues Progress deputy editor Conor Pope

New YouGov research published this weekend asked Labour members to choose their top three party leaders of all time. JR Clynes, who led the party for around 20 months from February 1921 until November the following year, scored a measly nought per cent.

The low score was, I presume, more the result of ignorance than a hitherto uncovered anti-Clynes sentiment within the party: at least, a similar survey for LabourList in 2015 suggests as much, with the former member for Manchester Platting receiving just six votes .

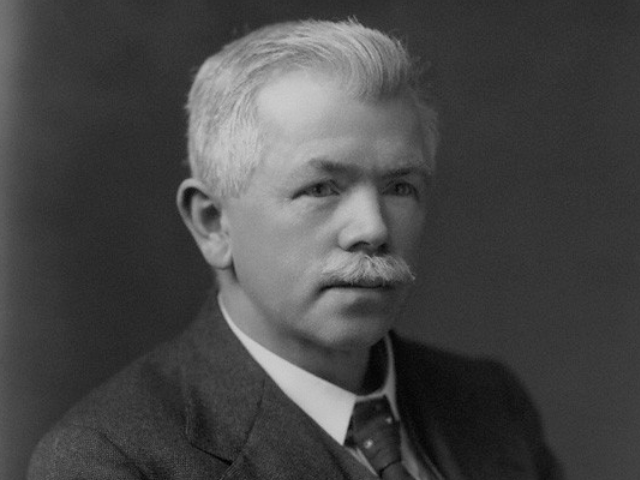

Clynes was born into a thoroughly working-class family in Oldham in 1869, beginning work in a local factory as a piecer at the age of 10. An autodidact, he saved up to buy a dictionary and book of grammar from travelling second-hand bookshops, and consumed the works of William Shakespeare with the help of a librarian from the local Cooperative Society library. It was through this process that he came to the realisation that the lack of access to a proper education for the poor was a political tool to keep the powerless, powerless.

Clynes entered the world of politics as a trade union representative – a job he had to maintain through his early years in parliament, when MPs did not receive a salary. While that soon changed, MPs’ pensions were still paltry when he stood down in 1945, and he lived the next, and last, four years of his life in poverty before he died aged 80.

Yet despite his diminutive reputation today, Clynes occupies an intriguing place in Labour’s history books. He was, in fact, the last leader before Labour became a party of government: his successor, Ramsay MacDonald, was Labour’s first prime minister. There is a decent argument to be made that it could – and, given how MacDonald turned out, maybe even should – have been him who became the first Labour inhabitant of No 10.

For while Clynes was not the leader who took Labour into power, he was the leader who oversaw the party’s real electoral breakthrough. In the general election of November 1922, Labour improved its share of the vote by nine points to 29 per cent, and returned an extra 85 MPs to the Commons – bringing its total to 142, and ensuring its place as the official opposition for the first time. This established the party as a major parliamentary force, changing the nature of British politics forever.

Since the breakthrough under Clynes, Labour has only ever won fewer than 150 seats once, in the exceptional post-split circumstances of 1931.

However, in those days, Labour MPs elected the party leader at the beginning of each parliamentary term. One week after the general election took place, the parliamentary Labour party elected MacDonald – who had previously served as leader between 1911 and 1914 – to take up the role as the first Labour leader of the opposition.

It was Clynes who, in 1924, moved the motion of no confidence that brought down Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative government and led to the formation of the first Labour government – albeit a minority one – under MacDonald.

Clynes should also be remembered as a champion Trot-basher. It was he who, as home secretary, barred Leon Trotsky from entering the country in 1929 – ostensibly on the grounds of not antagonising the Soviet Union, but also due to a concern that Trotsky might use his platform in Britain to whip up a revolutionary fervour, something which Clynes, a committed democrat, had no time for.

His belief in the parliamentary path to socialism was only strengthened by the general strike of 1926, which he had early reservations about, saying: ‘A national strike, if complete, would inflict starvation first and most in the poorest of the population. Riot or disorder could not feed them, and any appeal to force would inevitably be answered by superior force. How could such an action benefit the working classes?’

Speaking at the congress of National Union of General and Municipal Workers (NUGMW, a forerunner of the GMB) later that year, he made clear his objection to empty leftwing posturing that does nothing to actually improve conditions. While idealistic gestures are tempting in the short-term, he argued, without practical planning they achieve nothing: ‘Manifestations of solidarity are admirable, but solidarity without wisdom worthless, and the heroics of the first few days fighting fade into the sacred and subdued murmurs of defeated and distracted men.’

There is something here about the forgotten giants of the labour movement – especially on the moderate wing. I have dwelled on it regularly since interviewing Rachel Reeves about her biography of Alice Bacon for the December issue of the magazine: here was a figure who had played a huge role in the Labour party, and yet is barely remembered.

Clynes faces a similar fate. The only biography of him I can find, other than his own writings, was released a year ago. Called JR Clynes: A Political Life, by Tony Judge, I picked it up recently, but cannot recommend it: while mostly enjoyable, every page is strewn with grammatical and spelling errors, which must sadly cast some doubt on its historical accuracy. On the cover, the word ‘political’ is spelled with three ‘i’s. It is not the tome he deserves.

It is a shame, because it airbrushes important moderate figures out of our party’s history – another issue that has been playing on my mind lately. Our successes are only ever built on their successes, and it is critical that we have a proper understanding of where we stand. As Labour’s divisions become starker and starker, we cannot allow ourselves to be painted as outside of the traditions of this party when we have always belonged right within them. And, vitally, we cannot allow the lie to continue that pragmatism and values are some sort of dichotomy, rather than two things that are embedded within each other.

As Clynes, the working-class arch-pragmatist, wrote: ‘Labour serves the British people because it is a movement of the people. We have faced the people’s problems ourselves, in our own home and in the humble homes of our parents … Many of us have found in political life, not a splendid career, but an expression of our religion. A position has not been viewed as a job but as a cause.’

–––––––––––––––

Conor Pope is deputy editor at Progress. He tweets at @conorpope

–––––––––––––––

An excellent piece.

Phil Woolas has written an excellent biographical chapter on Clynes in “British Labour Leaders” which I co-edioted and was published by Biteback last year. Worth a read

During the 40’s Clynes’ desperate financial position was raised in Parliament. Churchill voiced his concern that a distinguished statesman should be reduced to poverty. Clynes was provided with a pension. I do not know if this was from public funds or by private subscription

Joined Labour in ’92, but never heard of him! Thanks for remembering a realistic achiever, of the kind we need now. ‘Manifestations of solidarity are admirable, but solidarity without wisdom worthless’- brilliant line.