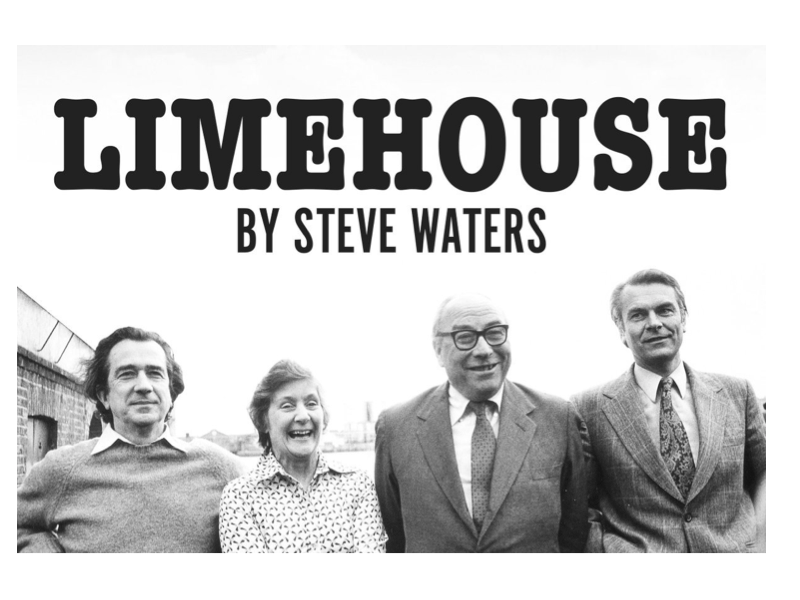

Steve Waters’ new play about the ‘gang of four’ is a reminder that Labour has looked over the precipice before – and recovered, writes Progress director Richard Angell

‘Labour’s f*cked’, pronounces David Owen at the start of Steve Waters’ new play at the Donmar theatre. Limehouse condenses weeks of high emotional drama about Labour’s predicament at the time into a morning on 25 January 1981, the day in which the ‘gang of four’ launched the Council for Social Democracy. Six weeks later it became a new party.

How it ever managed to happen is the main question for the production. These four ‘misfits’ have more tension between them at times than the Labour party conference floor that had turned against them so drastically and acrimoniously. Various games are played. They suspect each other’s motives, at one point or another, accusing each other of not really being Labour. Owen resents this claim just because he was born into a family not steeped in Labour movement history, unlike the others: ‘What have we become, a hereditary party.’ Roy Jenkins, the Welsh miner’s son, rehearses his love of the ‘liberal tradition’ – as is his love of Chateau Lafite, Europe and what his parents bequeathed. Shirley Williams, who lost her seat in 1979, has offers to go to Harvard and leave politics altogether – very appealing for this single mother. Bill Rodgers hits the nail on the head: ‘We will be hated, and rightly so.’ His voice betraying his own hatred for what he is about to do, after a hard struggle to convince himself it was necessary.

The play – brilliant and gripping – makes many obvious comparisons with the present day: a woman Tory prime minister, the former foreign secretary’s wife Debbie calling ‘voting Labour once again a minority pursuit’ and ‘Europe slipping away’. It feels in many ways a rallying call for a new group to create a new party. Waters is clearly keen on the idea. However, the play makes the counter argument better.

It seems clear that despite all the best – if disagreeable – intentions, the Social Democratic party was a failure. Where it did have real affect was its creation was the kick up the proverbial that moderate Labour desperately needed. However, within days of the break away the St Ermin’s Group of trade unions and the Labour Solidarity Campaign were created – see Dianne Hayter book Fightback, just months later Denis Healey beat Tony Benn to deputy leader and within two years Labour’s National Executive Committee was won back by moderates and Benn removed from the all powerful ‘home policy committee’. It did, however, take Labour more time to take on board the gang of four’s key message: not being the hard-left is not sufficient, the left will only win again when it has coherent social democratic story of national renewal that it is for, not a set of Tory and Trot policies it detests. The reluctance to face up to this explains the fourteen years it still took win even with Neil Kinnock as leader and Labour First running the NEC.

This should not be a lesson Labour moderates need to relearn. The historical parallels are turning out to be different from those Waters wants his audience to appreciate. Ed Miliband was the latter-day Michael Foot, not the current leader of the opposition. The young brother was respected as a former cabinet member and well liked by his colleagues – even those who had supported his more moderate rival in the preceding leadership election – but was unable to do what he knew Labour needed to do. In a toxic combination of settling factional scores from Labour’s time in government and a sentimentality for the soft left tradition he flirted with policy known to not work, and not supported by the electorate. He capitulated to the hard-left and and ignored outright despicable behaviour happening under his nose, this time Unite in Falkirk, rather than Militant Tendency in Liverpool.

Jeremy Corbyn has become the wake-up call the SDP once was. Progress and Labour First are working together better than ever before, local parties are being kept out of the hands of the hard-left, as are regional boards, the NEC and conference delegates. The modern day Bennites do not hold the NEC youth rep position, nor do they run LGBT Labour – they cannot even win chair of Tower Hamlet’s Labour party.

Limehouse is an entertaining evening and worth watching. Not least to remember that Labour has looked over the precipice before. It did however recover. In a postscript monologue, Debbie Owen reminds the audience it was immediately after the split Tony Blair was elected to parliament. So was Gordon Brown and Robin Cook, who went on to be towering figures in the creation of New Labour and the government that followed. But more importantly it reminds us of the agency we have on Labour’s fortunes. Those who #StayInLabour and fight can save the party we love. Those who stand in Labour’s darkest times could be the future of our great movement – so do not leave the pitch for the hard-left to run with the ball. That ‘one-stepping’ each other – to prove we are more leftwing than another friend or comrade in the moderate wing of the party – is why (moderate) Labour has fallen off a cliff. If we learn the right lessons – to make Labour politics about the voters concerns and a response based on Labour values – Labour can be saved again, and with it the country.

––––––––––––

Richard Angell is director of Progress. He tweets at @RichardAngell

Limehouse by Steve Waters is showing at the Donmar Warehouse

––––––––––––

Photo

Would like to see this play but tickets in short supply at Donmar Warehouse. Play text is available though…..