Delayed: the 2020 service from opposition

Like everything else the Labour party turns its hand to these days, the preparation for the Manchester Gorton byelection has not gone smoothly. The local party, having been suspended in the summer, still has a number of restrictions on it. The decision over when to go to the polls was delayed, as was the candidate selection – not that it helped the leader’s pick. Local member of the European parliament Afzal Khan was eventually selected, after Momentum choice Sam Wheeler (who was first briefed as a candidate the day Gerald Kaufman’s death became public) failed to make the shortlist.

Lisa Nandy’s appointment to lead the campaign is a sound choice, but not the one many members of parliament expected. Had your insider listened to some decidedly non-Corbynista comrades in the parliamentary Labour party, the wise choice for a small bet would have been on Lucy Powell, who won her own byelection in Manchester with a 16 per cent swing to Labour in 2012. Yet the leader’s office dragged its feet on the decision and refused to consider Powell for the role, frustrating frontbench colleagues and letting the days and weeks roll by without anyone in charge.

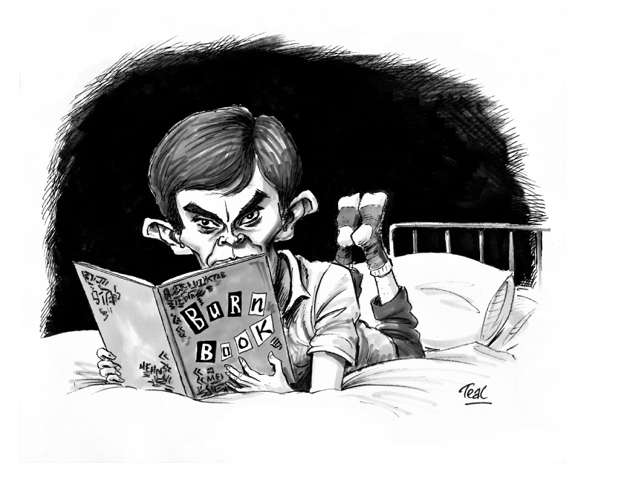

Like so many of her colleagues, Powell is considered persona non grata by the hardliners who now run the leader’s operation, by virtue of not being one of them. Her exclusion from the campaign is understandable in that regard. Yet if the rumours among gossipy Labour staff members are true, that Seumas Milne keeps a list of allies and enemies on his desk, divided up by their loyalty to Jeremy Corbyn – like a Mean Girls-style ‘burn book’ – Nandy would find herself in the same category as Powell. So what gives?

Delay and obfuscation from the leader’s office are often considered as signs of incompetence. But MPs have long since realised that it is far worse: it is a deliberate tactic. During the European Union referendum, Milne sat at home fending off requests from Stronger In for Corbyn to put some effort in. Throughout the leadership crisis which followed, Corbyn’s allies knew if they could delay him making a decision about stepping down, he could be convinced to stick it out. With byelections like Manchester Gorton, weeks without a political lead is better than giving an inch to someone who told Corbyn his leadership was untenable.

Some politicians glide through their careers like Teflon, with nothing sticking. With Corbyn, everything sticks to him and drags the party down. Yet he goes on, because issues like Brexit, winning byelections, or holding on to council seats are all minor compared to the broader blueprint for 2017: sticking it out until party conference. It is here where they will be hoping for the ‘McDonnell amendment’ to pass, which allows a hard-left successor to sneak on to the ballot at the next leadership election with minimal support from colleagues.

Despite vital local and mayoral elections in May, the efforts of Corbyn’s diminishing Praetorian guard are now focused squarely on holding out until September. Momentum is adding a national coordinator to its already 13-strong staff ahead of a relaunch as a cuddly, non-sectarian mobilising machine, and as Paul Richards profiled in last month’s magazine, potential successors are being lined up for a summer in the spotlight.

The Lansman tapes

An irrelevant Labour party, a female Conservative prime minister, and now, tapes. This 1980s revival is becoming more realistic with every passing week.

The infamous ‘Lansman tapes’ shattered Labour’s fragile ceasefire. On a tour of Momentum branches intended to make up for the fact that he had attempted (and failed) to kick half of their members out, the rabble’s founder Jon Lansman told Richmond Momentum – the seat where Labour has more members than voters – that plans were afoot to ‘change the nature of the party’.

Lansman’s claim that Unite would affiliate to Momentum to push for a hard-left takeover of constituency parties confirmed the worst fears of Labour MPs. Such a move, they think, would isolate Unite and threaten to split the trade union movement. The GMB and Unison, whose general secretaries are growing in frustration at Len McCluskey’s self-indulgence, have taken steps in recent months to shore up support for their own positions, so they can take their rightful place in the battle to save Labour.

If the rumours of a return to the Labour fold for the pro-Corbyn RMT are correct (the Fire Brigades Union is already back on board), we could yet witness an irreparable split in both the Labour party and the trade union movement which founded it. It would likely leave Unite and Momentum on one side, and Labour, the GMB and Unison on the other.

The suggestion is not wholly unfounded. Circulating among Labour moderates in the week of the Lansman tapes was a link to a 2014 story from Labour Briefing about the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy’s annual meeting of diehard Bennites. In the aftermath of the Collins review and the Falkirk scandal, the account of the meeting says members denounced the ‘backstabbing Unite has endured from some within Labour’ and how – without irony – there was widespread ‘disquiet at [Labour’s] failure to establish a decisive opinion poll lead’.

Most significant at the meeting was a discussion on a motion to ‘explore the possibility of a pro-Labour trade union party’. Having spent years falsely claiming Labour moderates want to ‘break the link’ with the trade unions, it is the hard-left who endanger it most. After all, who tabled that motion to explore a breakaway trade union party? Current Momentum director Christine Shawcroft, and a humble Labour party activist – and sole owner of Jeremy for Leader and Momentum affiliate Left Futures – named Jon Lansman. Splitters. Labour’s relationship with the trade unions has not looked this rocky in decades.

———————————

Cartoon: Adrian Teal

What a load of gossipy drivel, weaponised as a sort of bitchy attack on Labour. It’s time that Progress disaffiliated from Labour. Maybe Tim Farron needs help?

“The wise choice for a small bet would have been on Lucy Powell, who won her own byelection in Manchester with a 16 per cent swing to Labour in 2012”.

You forgot of course to mention that the Manchester Central by-election had the worst turnout of any since 2010, and one of the worst of all time. A paltry 18%.

Only 1 eligible voter in every 8 bothered to vote Labour in that election, despite being in central Manchester, for goodness sake!

I don’t have any axe to grind with Lucy Powell, but surely we should be aspiring to a better level of engagement with the electorate of Manchester Gorton than that?

It seems Corbyn has not yet learnt from Blair and Brown how to get a favoured supporter as candidate in a safe seat. after all Ms Kendal, the Milibands, Mandelson, Ms Flint, Ms Berger were all placed as candidates through the manipulation of the selection process. But that was all right because it was done by ‘moderate, progressive, centrists’.

And this ‘moderate, progressive, centrist’ group is so in touch with the wishes of the party that its candidate for leader got 5% of the vote in w2015 – and didn’t stand in 2016.

Some may ask if progress is hypocritical in its attachment to due process.